Choosing a tool for your data catalog can be daunting. The questions people usually ask focus on features and price, but in some cases, cost is the only consideration. The result is that companies often end up trying to use a tool they already have for a purpose that is entirely foreign to its intended use. A good example of this is companies trying to use MS Excel for their data catalog.

Data is an asset and metadata holds the key to understanding data. Failure to choose an effective data catalog tool guarantees that your data catalog project will fail. Here are some things you may not have considered...

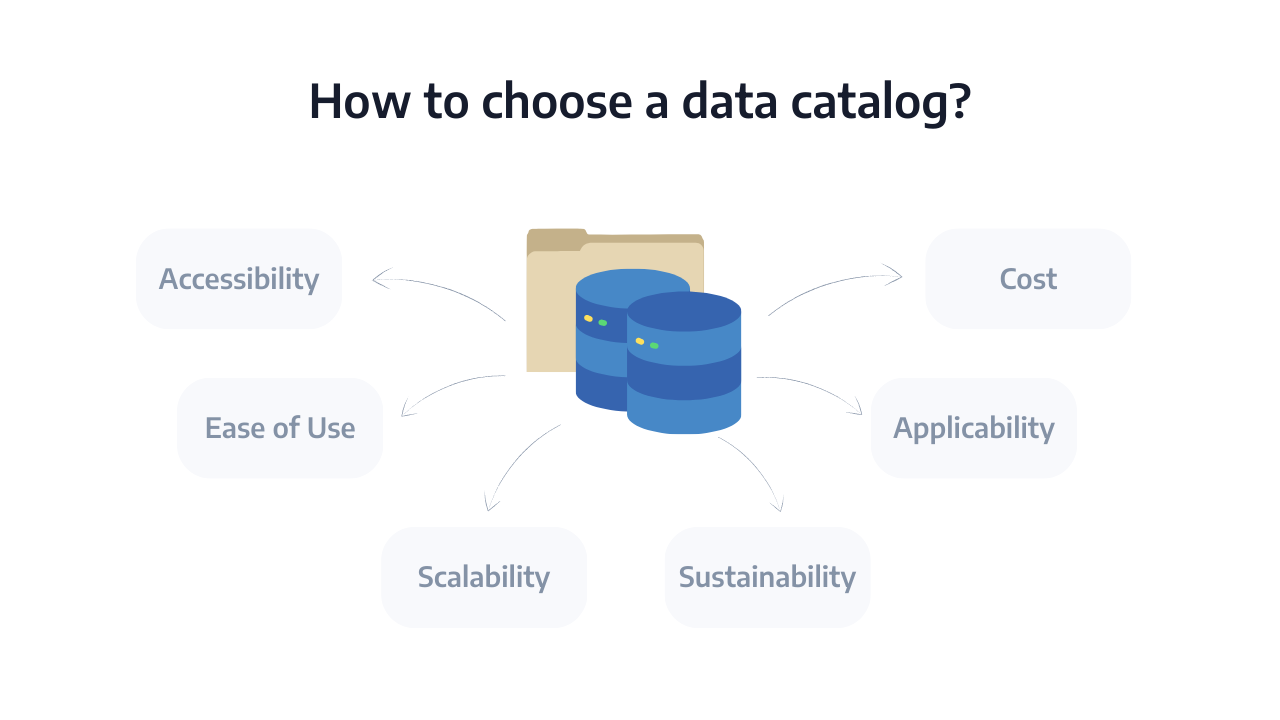

I am sometimes asked what tool I would recommend for use as a data catalog. My answer always starts with, “That depends…” and proceeds into a conversation about features and use cases. However, I believe that there are lots of other considerations that are rarely discussed.

A data catalog tool is an investment. Like any other investment, there is more to it than features. Later in this article, I’m going to use an analogy of buying a car to investing in a data catalog tool, but I wanted to use the example here as well. When you buy a car, do you consider only a few visible options such as color choices, leather seats, and A/C? Or do you also consider warranty, mileage, safety, resale value, and other less-visible characteristics? Choosing a tool is no different—there are other considerations above and beyond whether the tool can import metadata and hold a business glossary, for example. I’ve collected a few of these into this article.

Accessibility

Unless you’re a one-person shop, you need a tool that allows you to share your data catalog with others. This means that you need to manage access to the data catalog by your users.

In other words, the tool you choose must have the means to grant secure access to those who need access and keep all others out. An additional consideration is whether the tool needs to integrate with existing security and authentication policies in your company.

Ease of Use

You may want to consider how the tool will be set up initially and how difficult it is to maintain. How long will it take to install and configure? How many people will be needed to maintain the tool once it has been installed? Do you have the resources to support the tool?

After the tool has been installed, will it be easy to use? If not, others will probably not commit time to working with it.

Scalability

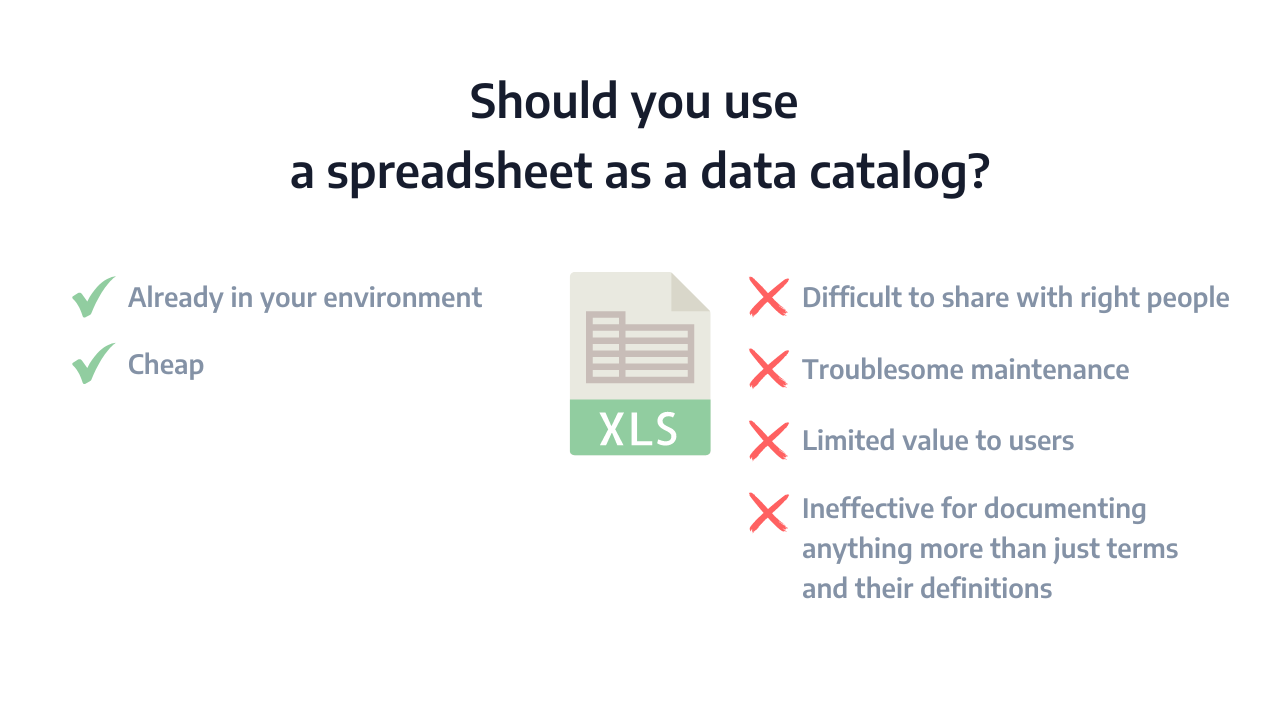

Unfortunately, some companies opt to use a tool not designed to be used as a data catalog. They have the belief that a data catalog is merely a collection of terms and definitions that people can use as a reference, and they don’t see a need to invest in it. Therefore, they think an existing app such as MS Excel will be adequate. There are several problems with this approach. The first is that it is difficult to share such a file with the appropriate group of people. What happens when new employees are onboarded? Are they told about the file and is it shared with them? Worse, what happens when the person who “owns” the file leaves the company? By default, access and use of a shared file will diminish over time.

Furthermore, the usefulness of such a shared file has limited value to users so even if it is maintained, use of it will invariably be low. If people can’t get the information they need, they will quickly revert to other methods such as messaging an expert directly for information.

Finally, a robust data catalog consists of much more than a simple collection of terms and definitions. Use of an ineffective tool guarantees that such information cannot be included and further limits the usefulness and reliance on the data catalog.

Sustainability

Other problems with trying to use a “shared file” approach to a data catalog include maintenance and versioning. Who is responsible for keeping the shared file up to date? What happens when that person leaves or moves into a different role? Or even when their attention turns to other, more pressing duties?

On the other hand, even if the shared file is kept up to date, there is a very real possibility that some employees will save their own local copy of the file—their version is no longer up to date. Worse, they can edit and share their copy with others, and you suddenly have multiple versions of the file in use. One of the primary reasons for having a data catalog is uniformity of understanding. Multiple versions of a shared file defeats this purpose. The result is wasted effort spent maintaining a resource of doubtful value.

Applicability

With all of that out of the way, we can consider the basic capabilities or functionality of the tool. Does it address your needs? This question requires that you consider your reasons for building a data catalog. What is important to you? Business glossary? Data dictionary? Data lineage? Privacy classification and regulatory compliance? Data quality?

When you start thinking about such uses, the limitations of using a tool not designed for use as a data catalog quickly become apparent. On the other hand, you should look at the features that do exist in the various tools you’re considering and decide whether you need them. If not, why pay extra for advanced features you know you’ll never need?

Cost

We now come to the question of cost. Unfortunately, companies often consider cost first, as if a data catalog were an afterthought rather than a valuable investment. Most businesses recognize the value of data as an asset, but relatively few recognize the need to manage the associated metadata. In other words, they have huge amounts of data but only a limited understanding of that data. If you don’t know what you have, how can you expect to use it effectively? And if people don’t understand what the data means, how can they use it to make informed decisions?

Your data catalog ought to be treated like any other asset with value. Choosing an inappropriate tool for your data catalog virtually guarantees that your data cataloging project will fail. The best outcome for such a situation is that someone will recognize the mistake and invest in a tool designed for metadata management despite the wasted time and effort incurred up to that point.

An Analogy: A Truck for a Housebuilder

Let’s consider a simple analogy to illustrate the major points I’ve talked about above.

Imagine that you are a housebuilder and you need to transport construction materials to your job site. You have several options including buying a truck for work. Pickup trucks range in price from $50,000 to $75,000; the price for a semi-truck ranges from $100,000 to $200,000.

Now imagine different approaches to selecting a vehicle. In one example, you simply don’t want to invest the money to purchase a vehicle, so you decide to use your personal vehicle which happens to be a small sports car. Obviously, the sports car was not intended to transport construction materials and any attempt to do so will end badly. This is an extreme example that illustrates what happens when you decide to use a tool you already have—even if it’s not intended for that purpose. When money is the first and primary consideration, poor decisions are made.

In the next example, let’s imagine that you rely on advertising claiming that you can “move anything” with a semi-truck. That may be true, but perhaps you don’t need to “move anything,” you just need to move some lumber. In this example, choosing the semi-truck would be a poor choice. It has a huge amount of capability that some people need, but you don’t need that capability and paying for it would be foolish.

The better approach is to determine what materials you need to move and buy the vehicle that best fits your needs. In our example, you’re moving construction materials for your house-building project and the pickup truck is ideal. After that decision has been made, you can shop around to compare the features and price of different trucks and decide which is the best choice for the price.

An Example from My Own Experience

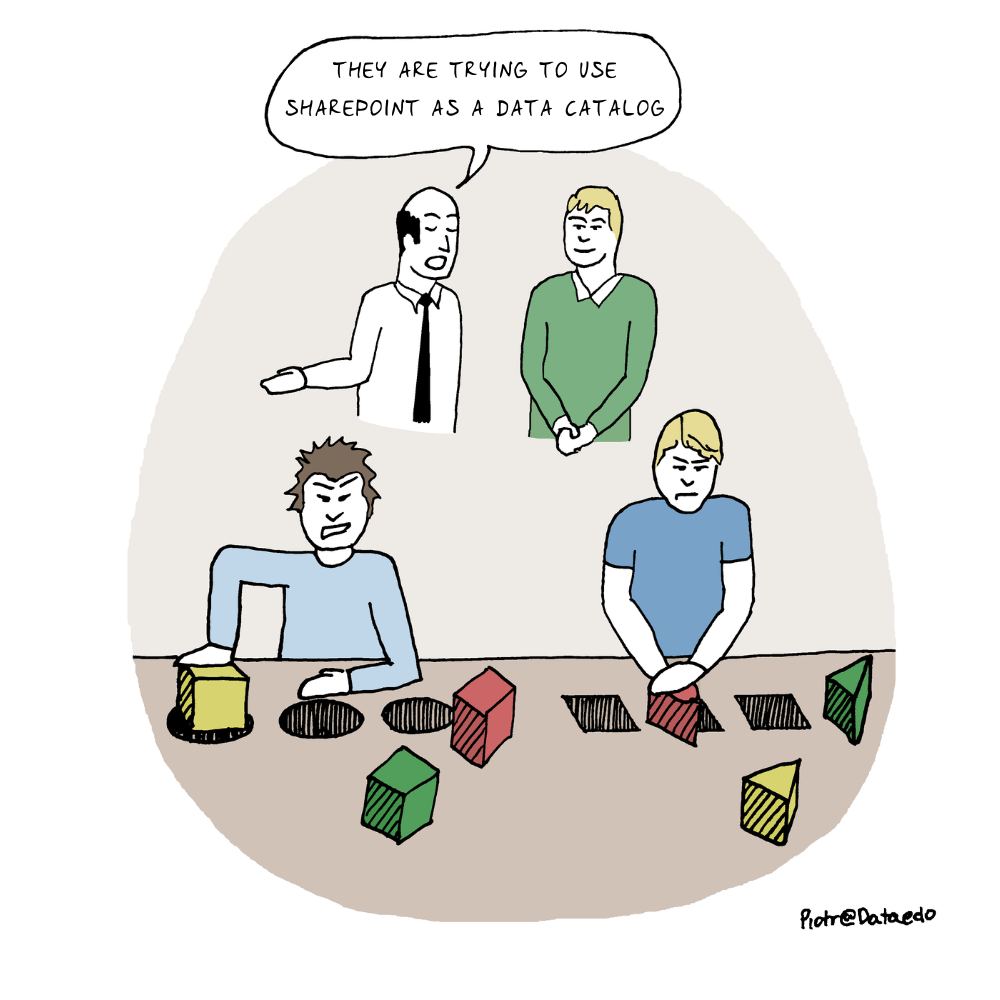

Several years ago, I started a new job and I was asked to create a knowledge management library, including a data dictionary and business glossary. I was told by my manager to build the library and data catalog in Confluence “because we have it, and everyone already has access.” I spent several months developing a functional knowledge base, but the data catalog eluded me. I was not worried, though, because I knew that Confluence was not the best choice for a data catalog. When I demonstrated the knowledge base to my manager, the question of security invariably came up. I replied that each user would need a Confluence license to maintain secure access. The reply was, “That’s not an option because we will eventually need to roll this out to several hundred users.”

My manager then told me to use SharePoint “because everyone already has access, and it won’t cost anything.” I disagreed, but for the second time, I found myself creating a prototype of the knowledge base in a tool not intended for that purpose. SharePoint is intended to facilitate file storage and sharing. While it is possible to create the knowledge base in the form of shareable files, SharePoint is not designed to support such a use case. Accessibility and maintenance are especially problematic. It was a case of trying to force square pegs into round holes and I was told as much when I completed the prototype.

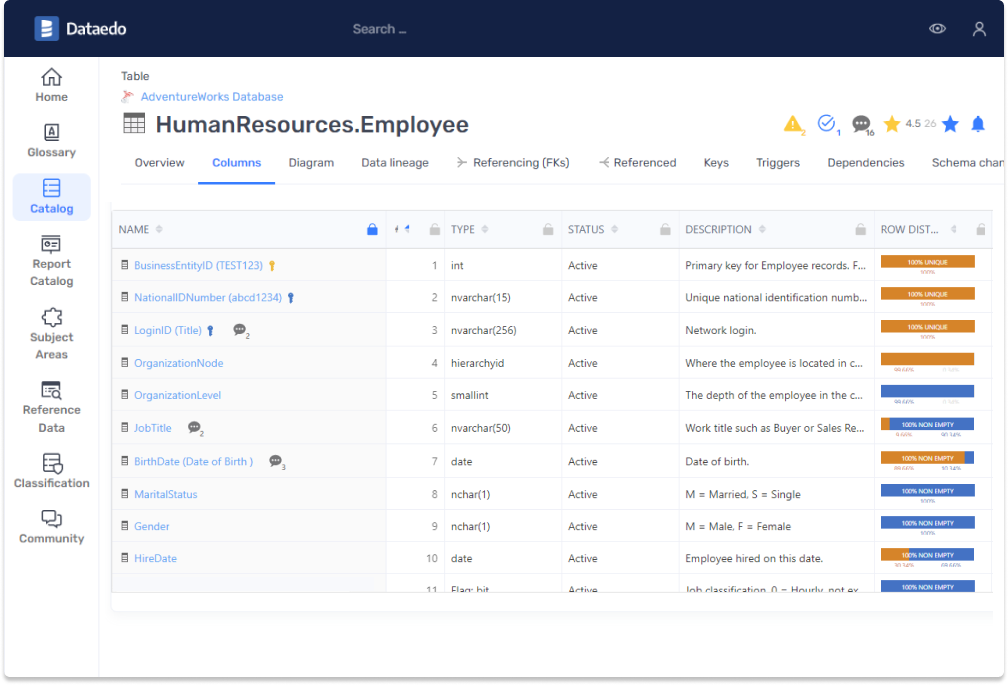

By this time, I had spent nine months on the knowledge base and was no closer to a solution than when I started. Fortunately, I had considered the knowledge base and the data catalog as separate solutions and had researched options for a data catalog independently. I determined that Dataedo met the requirements for use as our data catalog and procured it as a solution. Dataedo was easy to set up and simple to use. Even in the absence of meaningful descriptions from our source system, I was able to quickly write definitions for most of the objects (tables, views, and columns) in the data warehouse.

About two years after I began working with Dataedo, our company purchased a license for a more expensive metadata management tool. I approached this new tool with enthusiasm and spent almost a year implementing it as a knowledge base, a privacy and governance tool, and a data catalog consisting of both a business glossary and data dictionary. There were a lot of exciting features, including some that I really liked, but the tool was not focused primarily on the data catalog. It was functional, but the emphasis seemed to be on more “glittery” features and in the end, we determined that the tool had the wrong focus for our use case.

In the meantime, I had maintained our Dataedo license, so it was easy to move back and continue work on the data catalog in Dataedo. By this time, Dataedo had introduced the Web Catalog (now called Portal) which we implemented immediately. This made a huge difference in the useability of Dataedo at the company. Use was no longer limited to a small number of analysts. Overnight, almost, we rolled the data catalog out to a much larger audience who benefited greatly from it. As Dataedo introduced new features such as lineage, profiling, and classification, we discovered that these enhanced the tool rather than changing its direction and its primary use as a data catalog.

Conclusion

All of this is to say, “Determine what your needs are and find the tool that addresses those needs best.” In that process, don’t forget that there are considerations besides functionality that are equally important. Questions of budget should not be the driving factor. Price can help you decide between tools of otherwise equal capability, but basing the decision on cost alone is, I believe, a mistake in the long run. By limiting your tool choices to those that are free to you because they’re already used in the company (such as Excel or SharePoint), you set yourself up to fail—you can build a collection of terms and definitions, for example, but if you can’t maintain it or share it with colleagues, then you’ve wasted your valuable time and effort.

There is a popular saying in Spanish, “Lo barato sale caro.” Translated, this means “the cheap becomes expensive.” In other words, cutting corners, taking the easy route, and trying to get more for less, will almost always lead to losing time, doing more work, and paying more in the end. Plan wisely, evaluate thoroughly, and do what is best.

Richard Monk

Richard Monk